Unemployment does not exist

Impreparation exists

In Italy, graduating and finding a job is more difficult than in any other country in Europe

Have you ever been to one of those fairs, like Chance in Milan, Job & Orienta in Verona or Job Meeting in Padua? Like at a market, young people wander around looking for an employer, a buyer, anyone who promises them something to do. At the end of the day, when all else fails, they cling to the hope of a Master’s degree in the illusion that a horse dose of postgraduate studies can remedy an unpreparedness that has lasted for years, which unfortunately will prove to be irremediable, too deeply rooted to be corrected.

In Italy, graduating and finding a job is more difficult than in any other European country.

The reality is that while in all the industrial democracies of the world the long white-collar age is waning, in Italy the myth of the ‘fixed job’ still hovers and thrives. We are witnessing the rise in unemployment with growing apprehension, jobs have been dwindling for years all over the world and the possibility of finding a salaried job, especially for the younger generations, seems increasingly remote. Young people are threatened by the fact that they cannot even cross the threshold into the world of work and the professions.

White-collar workers are on their way to becoming an endangered species, and the white-collar age, which for two centuries, since the industrial revolution, has been gradually gaining ground in advanced societies, is now at an end. The clerical age, in its most modern version, originated about two centuries ago, when people began to consider time as a commodity, that is, when it became possible to buy people’s time instead of what they produce: goods, services and ideas. This happened with the birth of big business, and the necessity, following the industrial revolution, to have an army of millions of ‘dependent’ workers, whether blue or white collar, ready to sell their labour or their time at a fixed price, an hour or a month.

Dependent labour, as a modern version of servile labour, in the massive proportions it has assumed, is thus a contemporary phenomenon. Never before have so many men experienced a condition of semi-slavery with the illusion of freedom.

The Italian university system, in its rigid and almost immobile organisation, tries to live, to survive, even at the cost of dying. For a republic ‘founded on work’ to record the highest unemployment rate among the OECD countries, the most industrialised in the world, and to come last among all its European partners, is so paradoxical that it may sensibly require an amendment to Article 1 of the birth certificate of our Republic.

Rarely in history has a right so solemnly sanctioned and placed at the foundation of an entire nation been so profoundly and for so long disregarded, neglected and betrayed. Young people in Italy not only graduate six years later than their European counterparts, but also unprepared, obsolete, cut off from the international labour market and with serious difficulties in entering the domestic one.

In a job market now without borders, where companies increasingly value skills more than formal knowledge, Italy’s youth unemployment has only one cause: unpreparedness. We point to the higher education system and university training in this country as the main culprit for this national disaster.

Where does an economy like Veneto, which exports more than Greece and Portugal put together, go to find its managers to compete with companies all over the world? Where does Diesel, which taught Americans how to make jeans, find its managers? Where are the business leaders capable of facing the challenges ahead? A labour market that is hungry and thirsty for young graduates with an international background and work experience is being offered unprepared young people. Unprepared not only because they have no knowledge of what is happening in the world of organisations and professions, but above all because they do not know who they are. No one has helped them to nurture, to cherish their dream. After so many years of study, without a purpose, frightened, they have traded their passion, the happiness of doing what they love, for the false certainty of a fixed job and seek shelter in a job or try for years to win a competition, no matter where, no matter what for.

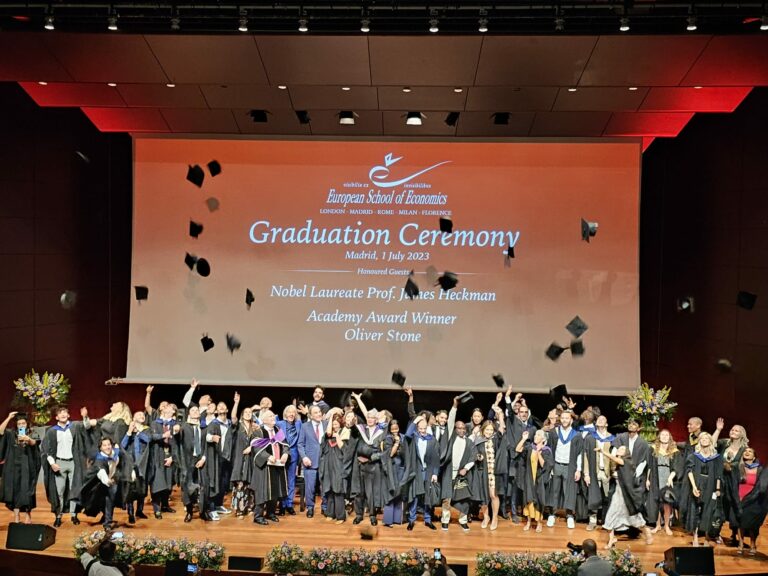

ESE students graduate in three years and are often placed before they even receive their title at the Graduation Ceremony. Eleonora Cazzaro, an ESE student, agreed during her studies, at the age of 22, to continue working in the Great Events department at the Fondazione Fiera Milano. Also Anna Cozza, during her 3rd year, had the fateful proposal from Diesel Industries of Molvena and Geox, one of the world’s three largest sports footwear industries, selected five recent ESE graduates for its Master’s course to train its future managers. But there are also great rewards for the most deserving students in terms of academic excellence. Caterina Cazzola, 21, from Verona, was selected to participate in the 100-day meeting organised by Pittsburgh University and reserved for students of all nationalities. At Berkeley University, the gold plaques won by ESE students such as Alessandro Nosei are still on display.

ESE affirms the right of young people to dream and see their dreams come true. Arriving at a job appointment and trying to get chosen, standing in queues, antechambers, looking for anything to do and a boss to pay you a salary, is below a level of dignity. A young person must be able to choose his job. No one should be put in a position to take any job for a living. To exercise such a right, one has to prepare oneself. We need international, pragmatic, multicultural schools of freedom that, in economics as in politics, will educate a new generation of business leaders, a young ruling class, pragmatic dreamers capable of harmonising the apparent antagonisms of all time: economics and ethics, action and contemplation, financial power and love.